Written by Rosemarie Parent using the Society’s archive materials and history books.

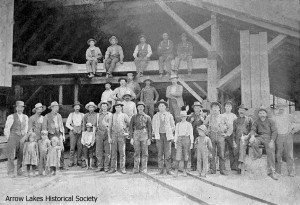

One of the most successful businesses to develop in the early days of Nakusp was the Genelle Brothers Lumber Co.

Marie Genelle was left a widow in Thessalon, Ontario with a family of fourteen children. Peter, John (Jack), Joseph and two girls, Addie and Sadie, were the older ones in the family, and together they decided to join in the construction of the CPR main line as it neared BC in 1884.

Peter, Jack and Joseph had gained experience in lumbering and although their schooling was nil (it was believed the men could only sign their names), they had been in the lumbering industry long enough to realize that there would be a vast demand for wood products when building the railway. There are any number of items that would be needed such as box cars, ties, trestles, bridges, snow sheds, stations, roundhouses, warehouses, water towers, sheds and fuel to name a few.

The family worked as a unit – the women cooked in the camps, the children did the chores, and the men made ties and eventually went into sawmilling.

With the completion of the rail line in 1885, Pete and Jack had amassed a sizable sum of money. They then decided to set up a mill at Tappen Siding between Salmon Arm and Kamloops in 1886. This venture was so successful that they started a mill at Yale. With each passing year, the firm grew larger. Instead of relaxing and enjoying the benefits of their hard-earned wealth, they became even more dedicated to expansion.

Jack and Peter heard about developments in the interior and the mining activities in the Slocan, so decided to come to the Arrow Lakes to view the situation. They marveled at the endless forest and decided to build a mill, the first in Nakusp, in the vicinity of the marina in 1893.

This was good news for Nakusp, because a crew was needed in the mill and the camps, which were set up to produce the logs and ties. J.E. Poupore, the Genelles brother-in-law, was the bookkeeper for the mill. The company was named Peter Genelle & Co.

Soon there was a frenzy of activity in the area, and railway construction was in high gear. Genelle had a contract for a million feet of lumber for Nakusp & Slocan railway bridges alone. There was also a heavy demand for business and home construction, and the Slocan mines needed material. A tug, aptly named ‘Nakusp’, was built by Jim Jamieson to be used to tow booms of logs to the mill.

The year 1894 brought floods and serious setbacks to the new mill. The company had to tear down their buildings and move the machinery further in shore. This caused a considerable loss to the mill, which was pressed at the time to get supplies out for the railway. The wharf cribwork, which was being constructed, could not be weighted down and a portion of it floated away. The planking had to be torn up and ropes attached to secure them. All supplies in the lower sheds had to be moved to higher ground. One of the buildings was razed by fire. A fierce gale sprang up, further weakening the wharf and causing numerous ties along the shore to be set adrift by the huge waves.

In total the company lost over 100,000 feet of dressed lumber besides a large amount of rough material as a result of the flood and windstorm. The company decided to dismantle the present mill and rebuild on pilings to prevent a further occurrence.

By 1895, the Genelle family was also involved in shipping. They had added another tug, the Henrietta, and with their first tug, the Nakusp, they could move substantial tonnage on large barges. When their operations shut down in winter, they moved their mill site in the Slocan. This provided them with income until production was resumed in the spring. Their horses were also used on the Sandon road where they had 10 teams hauling ore and one team hauling wood. The large horses could haul 5 tons per load at this time of year. This kept everyone happy garnering wages during the slack time at the mill.

The next years brought a furious rate of construction of various types of boats at the shipyard. The Columbia & Kootenay Steam Navigation Co. came to them with orders for boats on the lakes. The Genelles also had a contract for all the timber in the Nakusp & Slocan railway extension.

During the winter months of 1897, when all their lumber orders were caught up and the yards were full, the Genelles decided to build a more modern and larger mill just east of the present site in Nakusp. This became the largest sawmill in the Kootenays.

Because there was a need to supply material for the Columbia & Western Railway to extend the line from Trail to Robson West, it was decided to build a mill at a site called Wesley, near Castlegar.

Big changes came in 1899. Peter Genelle and Company decided to merge with Adolph Fisher and Louis Blue of Rossland to form the Yale Columbia Lumber Company with capitalization of $500,000. This huge concern would own and manage mills at Nakusp, Wesley, Greenwood, Phoenix, Eholt, Rock Creek and Long Lake. James Poupore was made general manager and Adolf Fisher was the manager of the Boundary Creek district. The head office was in Greenwood.

By 1900 to 1903, lumbering on the Arrow Lakes had become the major industry. In 1903, it was reported that the Yale Columbia Lumber Co. was applying to the government for cutting rights on the Columbia, extending 15 to 20 miles back from the river.

Competition with the other big mills at Arrowhead and Comaplix for the highly-valued timber was becoming a real challenge. American companies were also becoming interested in the industry because of the scarcity of merchantable timber in the States.

These were good times for the Genelle family. The outlook was bright for a happy, healthy and prosperous future. However, disaster was lurking on the sidelines. In 1904, Jack Genelle was still working on the towing part of the logging operation for the Yale Columbia Lumber Co. One day he tied up the tug near Bob Allen’s logging camp across from Miles Yingling’s farm in the Narrows (Burton area).

It was lunch time and Jack quickly prepared his food. Always in a hurry, he wasted no time in devouring the meal. Minutes later, he became ill and realized he was going to pass out. He managed to pull the cord to the whistle before falling out of the cabin onto the boom, his body half submerged in the water. Though the men had responded quickly to the whistle, by the time they arrived, Jack’s heart had stopped.

An inquest was held in Nakusp, but they could find no blame or wrongdoing in the incident. The death certificate indicated death by drowning. However, as the group at the inquest filed out, there was uneasiness. Everyone, especially the family, was dissatisfied with the conclusion of the court. There was no evidence that Jack’s head was ever under water.

An autopsy would have given an exact cause of death, but in a small town, an autopsy was unheard of. No one will ever know what actually had taken place and why. A ceremony was held in the Woodsmen’s Hall (upstairs in Abriel’s office where a large group joined to pay their last respects to one of the men who had made Nakusp his choice for a large capital investment which had provided income to so many in the area.

In 1905, the Bowman lumber Co. of Minneapolis brought all the Yale Columbia Lumber Co. holdings. Archive records show Genelles still holding many of the shares.

But in 1906, disaster struck again. Walter Scott wrote a few lines in his diary on June 14, 1906. “…Yale Columbia Lumber Co. mill took fire about 5 p.m. Lumber in the yard burned. At first it was thought all the town below the hill would be burned…” There was no fire protection, no volunteer fire brigade and no water system at this time in Nakusp. Some onlookers managed to save some of the property, and a few CPR cars were saved with the aid of a team of horses. The steamer Kootenay managed to throw some water from the pumps onto some of the lumber piles, which were saved.

The townspeople who lined up along the top of the hill felt certain that the town, a mere 14-years-old at this time, would not survive.

Peter Genelle stated that the company had no intention of rebuilding, and some families left for Genelle’s mill in Cascade. Thus the Genelle Bros. Mill, which became the Yale Columbia Lumber Co., was gone and a part of the early history of the area was over. It would take another businessman to venture forth to take advantage of the area’s great forest wealth. In so doing, there would be new employment opportunities and the town would be able to carry on.