Written by Milton Parent from Arrow Lakes Historical Society archives and an interview with Miriam Chandler.

The sky was dark. The air was cool and fresh, as one would expect on a mid-January morn. All was quiet and still, except for the spear of smoke that arose from the spaced farm houses and pierced the frosty mist. Eight inches of fresh snow had fallen overnight, coating the drifts and hiding the old trails.

Such was the scene, a typical midwinter morning; a harshness that had to be faced by the farmer, logger, businessmen, shipbuilder, the women and their children in the Nakusp area.

A lone figure sets out from Sleepy Hollow (Shakespeare Ave., Glenbank), a long-strapped bag over her shoulder. A long dress and long coat compound the difficulty of plowing her way through the narrow road. On and on she must go, farm after farm, the glimmer of coal oil lamps diffusing through ice-covered windows.

Ten acres this way, then twenty acres that way, finally the old Brouse station comes into view. A few more minutes and the little log schoolhouse finally appears and Miss Miriam (Mirrie) Chandler realizes her four-mile morning trek has ended. Another school day is about to begin.

In 1909, the children of Brouse were getting an education because of the tenacity of a teacher like Mirrie.

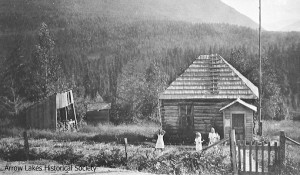

A small piece of land at Brouse was donated, Fred Wensley provided the logs and with the help of a group of fathers, the tiny school was erected in 1908. The windows were in, hand-split shakes were on the roof, the well was dug; the blackboard was up, desks situated, coal oil lamps, stove and a long wooden pointer – all was in readiness. The trustees then began to advertise for a teacher. (Note: even though the school was in Brouse, it was always called the Box Lake School).

Mirrie had been teaching in Rosebery, where Joe Parent Sr. had taken over the hotel for a while. Two of his daughters and his son Joe were going to school there along with the large Mooney family; enough children to keep the school open.

That summer, the Mooney family went on an extended vacation. Mr. Brothman, the school trustee, wrote Mirrie, who was spending the summer with her family in Nakusp, to say that the school would not open the next year. She applied for the job at the Box Lake School and was accepted immediately.

Like most rural schools, there were often many surprises to go along with the usual difficulties of small budgets, limited space and materials, especially in those pioneering days. Mirrie joked about opening day: she found that in her class of about fifteen children only three or four could speak English. All the rest spoke either Dutch or German. Henry Aalten says with pride that within a few weeks, most of the students were doing just fine and were well on their way to educating their parents.

One can only marvel at the industry of the teachers and pupils of this era. Chris Hamling remembers having to write everything on slates. Enid Shelling remembers that later on they had inkwells; not only was it difficult to write with ink on pulp-paper books, but her pigtails were dipped in the inkwells so often that she finally cut her hair off – for which she suffered a sound thrashing at home. Imagine the strain of trying to read and write on a dark winter morning by the light of candles and coal oil lamps.

A typical day started with exercises, which one performed while standing at one’s desk. All songs were sung without benefit or piano or organ. Subjects included grammar, arithmetic, reading, writing and spelling. The grades were from one to eight, all in one room. Many preschoolers often attended and were welcomed without hesitation.

Each week a boy was selected to keep the drinking pail full from the well; there was only one ladle to drink from, of course. The pail was kept in the entrance except in winter, when it was brought inside to remain ice-free. Also in the winter, a huge pile of jackets and boots was erected in one corner of this cloakroom. One can only imagine the furor and confusion at the end of the day.

The room was heated by a small square stove which sat on fairly long legs, keeping it up off the floor. It is not certain whether the boys looked after stoking the stove in those early days. Outside, they had a small woodshed which managed to burst into flames for some unknown reason, but no harm was done.

Of course, there were no sports in those days. In fact, there was no money to supply any equipment for such activities. The children were content with sleigh riding in the winter. In the good months, their games included kick-the-can, pom-pom pull-away and hopscotch. A set of swings was provided, but the girls had to be wary because the boys weren’t above loosening the knots to give them an unexpected descent. Also, one had to beware when passing by the well if the water boy was filling the pail at that moment.

Enid well remembers the long wooden pointer that Miss Chandler kept at hand. A strong crack on her desk brought the class to attention with startling results. It was this ‘jumping out of my skin’ reaction that prompted some to contemplate placing this little piece of wood on the fire. However, this was never done. The worst punishment that Miss Chandler perpetrated on her class was writing lines.

After the long day was over, Mirrie would close up and make her way along a short path to the Wensleys. Mrs. Wensley always had a pot of tea ready, which would provide her with the energy she required to set off on the four-mile journey back to Sleepy Hollow. Over the nearly four years Mirrie was at Brouse, she got to know everyone and they kindly offered her transportation to and from Glenbank as often as possible. This necessitated her conveyance on every type of beast or contraption, not the least of which was a three-wheel CPR speeder.

Feeling that she had served the Brouse community well, Mirrie took advantage of the opportunity to carry on in her vocation closer to home in the town of Nakusp. A brand new school had just been constructed and her application was accepted, much to the joy of the youngsters. Mirrie taught all through the war years, then in December 1918 decided to move with her family to Victoria, where she lived and worked for many years. In 1978, she and her sister moved to Trail where she lived in Kiro Manor.

Mirrie Chandler was born in Ramsgate, County of Kent, England, on March 21, 1882. She died in May 1989, at the age of 107 years.