Compiled by Rosemarie Parent using Arrow Lakes Historical Archives records and the history books produced by author Milton Parent

In 1907, a mill/logging industry was started at Summit Lake – a beautiful spot halfway between Nakusp and New Denver. Originally on the route taken by the Slocan mines to bring ore to the Arrow Lakes its potential for a complex but pocket-sized rendition of a coast-type operation was apparent. The lake was small but adequate for log booming facilities. Within a few short miles, a vast forest of fine timber, comprised of most species, could be harvested using horse power or mechanized methods. The original timber limits were held by J.P. Gallagher and F. Pelton but in the spring of 1907, J.R. Boynton, managing director of the Elk Lumber Co. at Fernie, bought the property. It was estimated that over 100 million feet of standing timber to be used for poles, ties and lumber would be available from those limits.

A site was cleared and construction started on a mill that was double-sided; the lumber section was separated from the tie area. George Robinson was the manager at this time but with costs mounting some of his backers decided to pull out. Fortunately, a group of men from Rhineland, Wisconsin, were travelling around the Kootenay looking for business investments. They took the train from Rosebery and stopped at Summit Lake to investigate the operation. George invited the men to stay the night at the camp where they discussed the predicament he was facing because of the recent financial withdrawal. The next morning, three of his guests, McEachern, Smith and Brown, offered to subscribe the necessary $30,000 needed for the take-over of the residue stock.

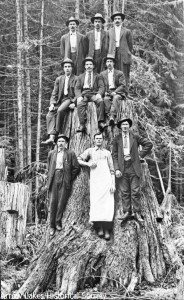

The mill, now named ‘The Summit Lumber Company’, was again able to resume with building plans. The company owned fourteen limits around the lake and already had orders that would keep the mill running for a year. The plant, which had a capacity of 40,000 feet a day, employed a work force of 40 men and would be operational by July 1907. Although the mill was twelve miles away, it provided employment for loggers and mill-men from Nakusp. Tom Allshouse was working at Fernie for the Elk Lumber Co. as a timekeeper and stocktaker. Their association with the mill at Summit Lake resulted in Tom becoming interested in this operation. He bought some shares, was made secretary-treasurer of the company, and moved to Summit Lake in January 1910.

Frank Thorpe’s father came in 1910 to be a helper to Mr. Burkett, the millright at Summit Lake. By 1912 he had moved to New Denver (15 miles away) but still walked to work every Monday morning. Frank was very young then but remembers that they had a large three-tiered bunkhouse that he visited often. The crew made much of him and the cook would feed him treats.

A school was started which was attended by Frank, his sister, two Marshall children, two Swedish lads and the teacher’s daughter. Frank was really too young but in the early days to make up enough enrollment to have a school, youngsters were encouraged to attend before the required age of six.

Winters were harsh here and one year, when the snow was 9 feet 3 inches deep at the CPR station, to keep the track clear on the rail line, two engines were put together to push a plow. However, a unique system of getting logs to the lake was with the utilization of such an abundance of snow. A path was tramped up the side hill; then a log was hitched behind a horse on a mild day and dragged down this trail. When the snow froze hard overnight, logs were sent down this chute. As the snow depend, the sides built up higher and higher which gave the corridor better walls. As the logs slid along the surface, heat was generated which would melt the lining slightly. This would refreeze quickly forming a perfect log cradle for the months of work ahead.

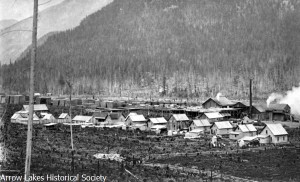

Summit Lake had everything that was needed to make this the perfect spot for a mill. The CPR had a railway with a little station and a wye for turning the train. The town was situated on a flat place of enough acreage to provide a mill-site, mill-yard, bunkhouses, rail-yard, pole-yard, town and grazing area. Although the lake was not deep, the level was quite constant, assuring towing capabilities for the transport of the logs to the millpond. To operate the logging division at maximum performance, a floating camp was constructed at the south end of the lake right below the cutting area. It was complete with bunkhouse and cook house.

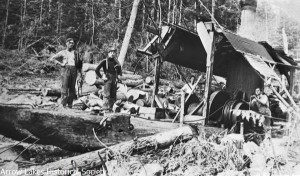

A unique logging system was used with a high lead to yard the logs. Apart from the Big Bend area, this was the only equipment of this kind to be utilized in the West Kootenay. A large donkey engine was operated to do this work. Preparing the spar trees required skill, strength and nerve. Charlie Martin, the boss of the camp, performed this job. He would chop and saw the top of the tree off and then sit on it while it swayed back and forth just to show his nerve!

Two little boats provided the power for towing the booms the short distance to the mill. The steady pop of the motor on one of them while pulling a boom prompted the name ‘Popper’.

The mill used a circular saw head rig with the carriage operated on gunshot feed. A planer mill took the air-dried lumber from the yard, reworking it into tongue and groove vee joint, shiplap and mouldings. The mill boasted a small electric generating plant which provided lights for the community. Though it did not produce a large amount of power, the people appreciated what was made available.

One man, John Grigg Sr., a fireman at the mill in 1917, would walk from his home in Glenbank in Nakusp at 4 am. Monday morning in order to be at camp in time for breakfast. He would walk out for home Saturday afternoon after his shift but if lucky sometimes got a lift on a speeder.

In 1920, a fire destroyed the mill, fortunately with no injuries, however the mill did not open again. Allshouse and bookkeeper, George Robinson, decided to concentrate on their pole-yard, which included pilings and ties. This became a sizable yard and a major operation. One of the feature loads of poles contained a 102 foot flagpole destined for England.

During the disastrous fire season of 1925, the pole-yard was entirely burned. Some thought that coal-burning locomotives spewing out hot coals were the cause but conditions of extremely dry grasslands and high temperatures had produced ideal fire conditions and this added to the problem. A terrible wind came up and spread the fire even to the islands, where some of the men and forestry people had gone for safety.

Chris Hamling Jr. was working on his dad’s ranch at Box Lake when he noticed the smoke and headed up the track to the mill to see if he could help. The forestry agent, old Jack Frost, walked up with him. At this time it was about two acres in size and Chris helped two other men who were pumping water onto the logging road there. But a terrible wind took the fire over onto both sides of the road. When the water quit running they went to see what the trouble was and found all the men were in the lake. Rabbits were running everywhere, squealing and howling.

“…Allshouse and Alpsen picked us up in their big launch and while towing a big raft that his boat fit into and we ran out towards the island. The raft caught fire too because the tremendous wind caused by the heat brought sparks that soon flamed up. We had to go to the second island because the flames were blowing right across the lake. We used buckets to smother the sparks flaring up incessantly. A workshop at Summit had a galvanized roof and sides but there was about a half a barrel of gas in it. It blew up and this galvanized iron flew right over the top of us in all shapes, twisted and bent. There was so much wind that pieces of sixteen foot lumber were flying through the air, end over end. We had to keep ducking under the water to snuff out the ash that kept falling on us….”

This disastrous fire resulted in hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost timber but happily no lives were lost. Years of litigation followed between the CPR and claimants. Finally in 1929, Nels Alpsen and Thomas Allshouse signed a release as plaintiffs in an appeal case against the CPR for damages against the company for the forest fire which destroyed their timber limits near Summit Lake. They received a cheque for the amount of approximately $13,000 for their losses. Other plaintiffs who received settlements were – the Ontario-Slocan Lumber Co., $6,000; Midlake Lumber Co., $13,000; William Hunter, $3,200; and the Doukhobors, $600.

This beautiful site that had so much promise never did become the large mill and pole yard complex initially expected. The photos of the town and mill show just how much was lost forever.