Compiled by Rosemarie Parent using the Arrow Lakes Historical Society archives and history publications.

Sidney Leary, an orphan from England came to Ontario in 1907. He first worked on the prairies and Eastern Washington harvesting grain then made his way into the St. Mary River country in BC and learned how to ride logs. It was an enjoyable challenge when he heard that the Arrowhead and Comaplix mills were active, Sid came there to apply for work. He built his own camp and started contract logging for the mills there. A floating camp with bunkhouse, cookhouse and office was built. Because it was portable, he was able to travel to any destination required, which allowed for flexibility other groups did not have.

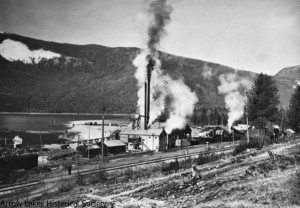

When he found it difficult to get buyers for his logs, he decided to build his own mill. Elmira Horton, who was the manager of the WW Powell Co, manufacturers of lumber and match-blocks in Nelson, financed Sid in the building of the White Pine Lumber Co. mill in Nakusp in late 1920. A lease of land was obtained from the CPR, which was bordered on one side by the town and CPR wharf and on the other side by the Lindsley pole-yard. The Dennision-Hutchison Shingle mill, which had been on this land had gone to Arrowhead at this time, so Sid used this building to set up a lath mill.

It is not known where the equipment and machinery for the White Pine mill came from but it was a steam boiler system with a large engine to power a line shaft that drove all the saws and gear mechanisms. The head rig was over and under circular saws matched with a cable-driven carriage. Cutting was almost exclusively two-inch pine planks, that were required to be clear of knots for the manufacturing of match blocks. Business was good and it was difficult to keep ahead of orders.

In 1929, the White Pine Lumber Co. burned to the ground leaving Sid with $20,000 in insurance to rebuild. The planer mill and some other structures survived the fire, which helped him with the decision to complete the project. The new mill helped families with steady employment during the years after the fall of the stock market and the war years of hard times. Sid had access to timber limits of the Upper Arrow Lakes and steady orders kept the mill operating. The same ‘line shaft’ system was used as in the former mill. Steam was generated solely by the burning of sawdust and shavings that were carried by blower and conveyor belt to the furnaces. A smaller steam engine, located right in the planer mill, provided the running power for this section.

Jerry Morehouse, Sid Leary’s bookkeeper, said that companies kept changing their names to save on taxes. Each time they did this, a fresh set of deductions could be invoked. This may have been the reason the Big Bend Cedar Pole Co. applied for a name change in 1942, but the request was granted and the new name, Big Bend Lumber Co., came into being. Jerry also said that Sid himself had no shares in the company thinking it more prudent to put them in his wife’s name. Beside Florence, one other share each was held by Jerry Morehouse and Bert Sundstrom. This was done for protection of their personal holdings.

The mill was the mainstay of employment for the men of Nakusp and orders came from far and wide. By 1945, Sid began to hire several of the Japanese who had been sent out to internment camps in the area. Many were coast loggers and very good workers. After the war, they were told that they must go back to Japan or go back east. It was at this time that the entrepreneurial spirit of these men came to the fore. Combining their experience with hard work brought success to them as contractors and even small mill-owners in the Nakusp area. Perhaps B.C.’s greatest flood year, 1948, the Big Bend Lumber Co. had to close their mill till after the waters receded and as well move the boom so that it would not jam into the buildings that were now in a good depth of water.

Sid Leary died in 1950 after he suffered a heart attack. Florence had no choice but to turn to her brother Ron Jordan to look after the mill operations. One of the first items to take care of was the replacement of the old Tourist tug because it couldn’t pass government inspection. The Kee-Tow was brought in. Byron Crowell, who had captained some large vessels at the coast, was contacted to captain the boat. This brought the return of the Crowells to Nakusp and was the best year yet when the mill cut 5,500,000 f.b.m. In March of 1951, Florence sold the mill to a new company headed by ‘Wick’ Gray. It was the start of a new era on the Arrow Lakes.

A year later, Columbia Cellulose Corporation signed an agreement to allow them to harvest nearly one billion feet of timber in the area that would be flooded when the dams were built in a few years time. It was estimated that it would be another two years before mills could be built and operational at Castlegar, therefore Celgar took advantage of their position as license holders to buy-out the William Waldie mill, Big Bend Lumber Co. and Columbia River Timbers Ltd. of Sidmouth. In Nakusp, Howard Jeal was manager, Jerry Morehouse, office manager and Ron Jordan was woods manager in this new arrangement.

When the pulp mill at Castlegar was established, it was necessary to find a way to bring in the logs from above Revelstoke to the mill. River drives were found to be the answer to move the huge bundles of logs from above Revelstoke to Castlegar. This was very dangerous work and many young men had to learn while on the job-a condition that took more nerve than some could handle. At times, enormous log jams occurred and the men had to get them apart without getting hurt in the process.

The Columbia River had calm waters in many areas but also several stretches of bad rapids, which could combine with huge boulders, shallow spots, log bars and whirlpools. Rex Thorp, who had a degree in forestry, was put in charge of this whole operation. The problem was that there was no previous experience in this type of logging. Bundles were made up of logs that were loaded onto a truck and then bound with straps. They were dumped onto a river bar or bank to await the spring waters. Hundreds of bundles then float down river and are corralled into a catch boom and sorted. Large booms are made up to be towed to holding bays where they are reassembled to be taken through the Narrows at Burton. There they are again restructured for a large tow through the lower lake. To read more about the river drive, the Arrow Lakes Historical Society published a book in 2006 called ‘Caulkboot Riverdance’ which was written by Milton Parent.